“On the basis of brute fact no predication is possible.”

-CVT, Christian Theistic Evidences pg. 59

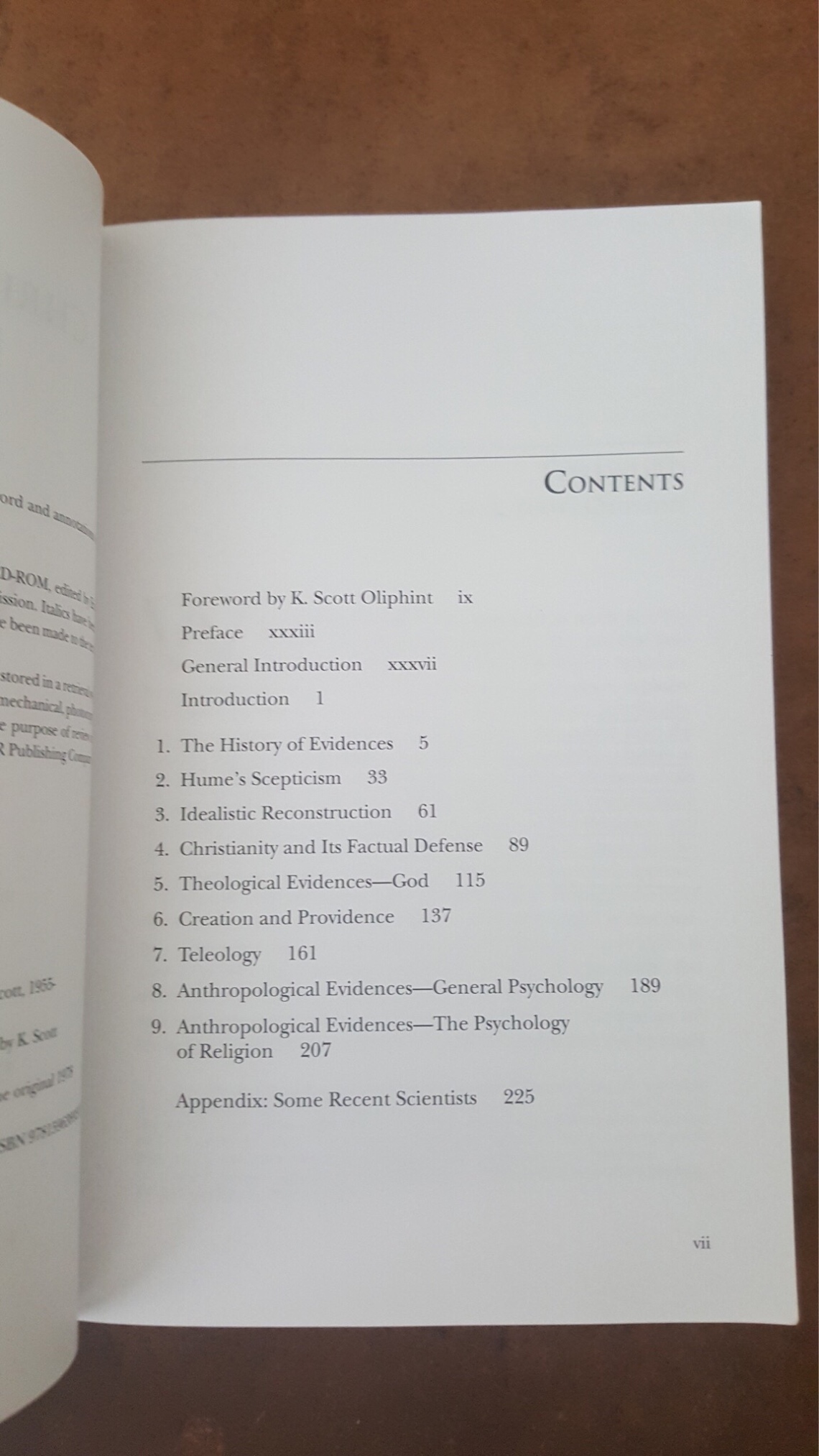

This book is Gold! As far as getting to know Van Til’s thought in his own words, I might start recommending that people read this book before his others like The Defense of the Faith or An Introduction to Systematic Theology.

In classic Van Til fashion, the title leaves something to be desired, but also in Van Til fashion, this book was originally a class syllabus. Van Til started his teaching career at the newly founded Westminster Theological Seminary with his course on “Evidences” in the summer of 1930. Teaching this course eventually gave rise to the first edition of this syllabus-turned-book in 1978. As Dr. Scott Oliphint says in the foreword to the second edition, “It was this syllabus that began, in earnest, Van Til’s Reformed reorientation and reformation of Christian Apologetics”.

A better title for the book might be, “No Brute Facts”, because while CVT does investigate theistic evidences and the Christian proponents of Empiricism, Common Sense Realism, Kantian and Idealistic apologetics, his main thrust and interest is to show that “… it is impossible to reason on the basis of brute facts”. With this in mind, the title might be a bit misleading. This is not a book- like John Frame’s, Apologetics- that seeks to reformulate theistic arguments in a presuppositional framework. Rather, it’s classic Vantillian presuppositionalism,

“Everyone who reasons about facts comes to those facts with a schematism into which he fits the facts. The real question is, therefore, into whose schematism the facts will fit.” (pg. 68).

A major part of Van Til’s appeal is not merely his philosophical acumen or unique insights; many are drawn to Van Til’s apologetic method because he seeks to bring apologetics back under the influence of theology, where it belongs. Van Til doesn’t think it wise or pious to defend “theism” with apologetics and argue for Christianity from evidences, instead we should defend and argue for Christian theism, with evidences and apologetical arguments.

“Evidences, then, is a subdivision of apologetics in the broader sense of the word, and is coordinate with apologetics in the more limited sense of the word. Christian-theistic evidences is, then, the defense of Christian theism against any attack that may be made upon it by “science.” Yet it is Christian theism as a unit that we defend. We do not seek to defend theism in apologetics and Christianity in evidences, but we seek to defend Christian theism in both courses. Then, too, in the method of defense we do not limit ourselves to argument about facts in the course in evidences nor to philosophical argument in the course in apologetics. It is really quite impossible to make a sharp distinction between theism and Christianity and between the method of defense for each of them.” (pg. 1).

Now, if you’re familiar with Cornelius Van Til at all, then you’ve heard people talk about how difficult he is to read. I disagree. But If you’ve found him to be hard to understand or found his style, or lack of style, a barrier in the way of you getting into his work in his own words, then this second edition is for you. P&R publishers have been reproducing CVT’s works with footnotes by two of Van Til’s students. In this volume, Dr, K. Scott Oliphint does a great job of explaining outdated philosophical jargon, providing context for some of Van Til’s more obscure phraseology, and explaining how Van Til’s critiques equally apply to thinkers that came after him, like Alvin Plantinga.

I really enjoyed this book and I recommend it for anyone who wants to understand Van Til and presuppositional apologetics. Grab it Here to support my book reviews so I can buy more and continue to help you find the good ones.

I’ll leave you with a couple of my favorite gems,

“The indispensable character of the presupposition of God’s existence is the best possible proof of God’s actual existence. If God does not exist, we know nothing. For Descartes’ formula, “I think, therefore I am,” we now substitute, “God thinks, therefore I am.” The actuality of God’s existence is the presupposition of the intelligibility of the concepts of possibility and probability.” (Pg. 77-78)

“If we take apologetics in its broad sense we mean by it the vindication of Christian theism against any form of non-theistic and non-Christian thought.” (Pg. 1)

“We know that Butler says he “supposes,” i.e., presupposes, the “Author of nature.” We now see that he “supposes” it because he thinks God’s existence can be established by a reasonable argument. On exactly what then does this reasonable argument rest? Is there another foundation beside experience and observation from which we can reason from the known to the unknown? If there is, why may we not use that other foundation as a starting point for our reasoning with respect to a future life? If there is not, is not our argument for the existence of God of just as great or just as little value as our argument for a future life? What meaning is there then in the idea that we “suppose” an “Author of nature”? Are we not then for all practical purposes ignoring him? In other words, if God is presupposed, should not that presupposition control our reasoning? And in that case can we be empiricists in our method of argument?” (Pg. 19).

“There are others, however, who use Kant in order to refute Hume, and then seek to refute Kant with the help of Kant. These men think, and we believe think correctly, that every appeal made to bare fact is unintelligible. Every fact must stand in relation to other facts or it means nothing to anyone. We may argue at length whether there is a noise in the woods when a tree falls even if no one is there to hear it, but there can be no reasonable argument about the fact that even if there be such a noise, it means nothing to anyone. There is, therefore, a necessary connection between the facts and the observer or interpreter of facts.” (Pg. 67).

I enjoyed this book myself though it wasn’t necessarily Van Til’s best work in my opinion

LikeLike

What’s his best in your opinion? I’d say A Survey of Christian Epistemology

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know I still need to read Survey of Christian Epistemology. I thought I enjoyed his “Christian Apologetics” the most: https://veritasdomain.wordpress.com/2011/02/22/book-review-christian-apologetics-by-dr-van-til/. I thought it was the most straight forward and clear work by Van Til without his usual tangents and side battles with all kinds of theologians, apologists, philosophers, etc.

LikeLike

I still gotta read Christian Apologetics

LikeLiked by 1 person

I imagine the way I feel about wanting to read Survey of Christian Epistemology is how you feel about Van Til’s Christian Apologetics! God bless you brother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate you taking pictures and posting them in this article. It gave me a sense of what the book was about. Thanks for posting!

LikeLike